This, Not That

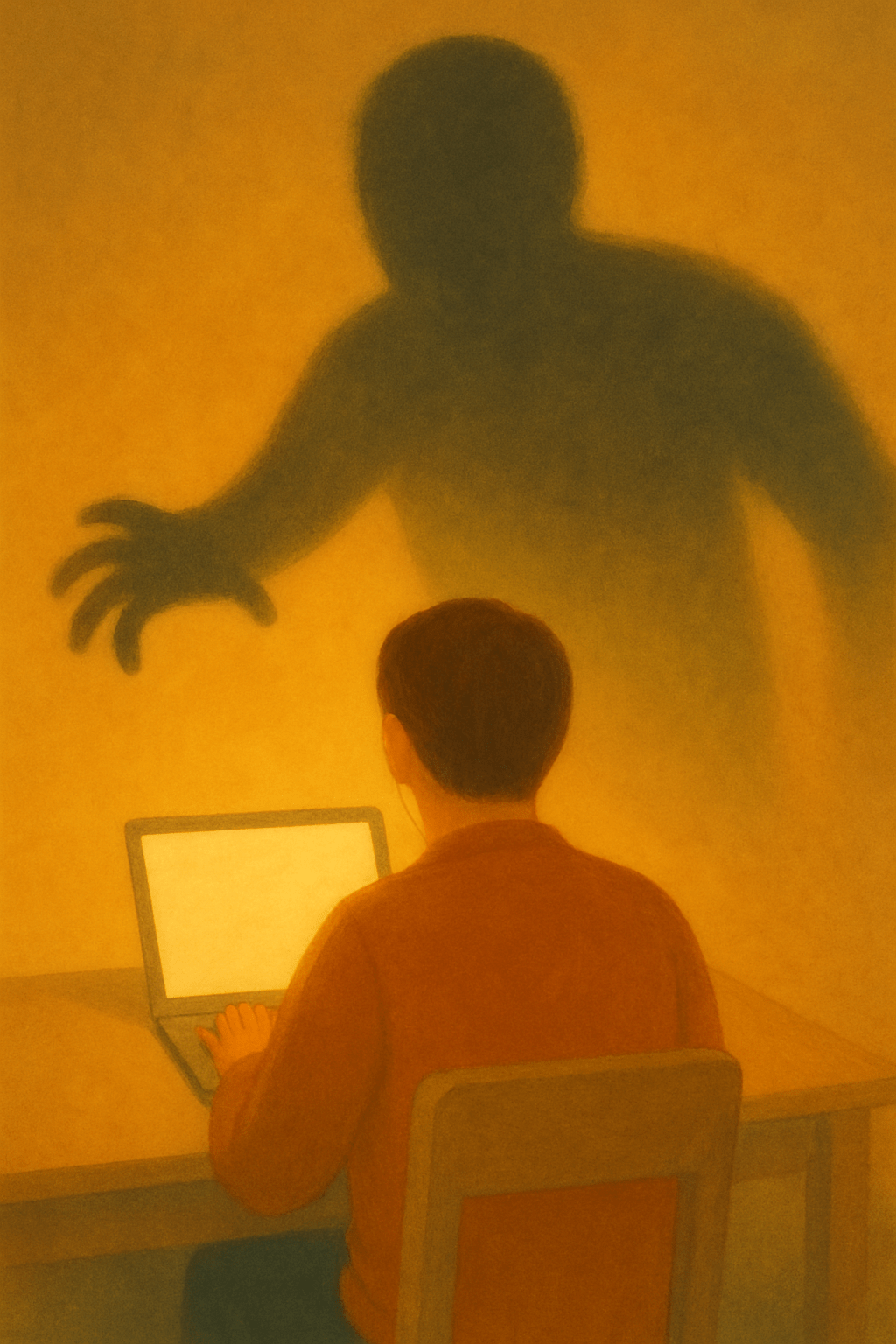

Ah, scope creep. The unwelcome guest that sidles into your project without an invitation, helps itself to your time, and somehow convinces everyone it was meant to be there all along.

It's called "creep" for good reason. It doesn't knock politely. It just oozes in sideways, one harmless little request at a time, until suddenly you're wondering how a simple strategy project became a sprawling mess of half-finished deliverables and you're working weekends and hating yourself for it.

We've all been there. I first started seeing the effects of it—really feeling it—back in the early stages of the agency I was at before I went freelance. We were still working things out, still introducing UX stuff into our offering, and scope creep was practically a regular team member.

I was a few weeks into what should have been a focused UX strategy project when the little extras started appearing. Could I just have a quick look at their sitemap while I was thinking about user journeys? A couple of additional rounds of amends on the recommendations. Maybe a brief review of their existing content approach, since it was all connected anyway.

Each request was small. Reasonable. "Won't take long."

But slowly, I found myself spinning more and more plates. The strategy work that was meant to be the core deliverable kept getting pushed aside for these quick additions. And once you're juggling multiple streams of work on the same project, saying no to the next small request becomes surprisingly difficult.

By the end, what felt like helpful collaboration had quietly expanded into something much bigger than anyone had originally scoped for.

The problem wasn't them. The problem was us, and a proposal that said what we'd do but never bothered to mention what we wouldn't.

The Cure for Creep

I've tried so many different things over the years to avoid this kind of mess. But I keep coming back to this amazing technique that I first learned at the agency Clearleft. They're a clever bunch of sausages, and when I was freelancing there, it was introduced to me in a show and tell from Katie Wishlade.

Katie later went on to Berst, another ridiculously talented little crew. Since seeing that team use it so effectively in all parts of projects, it's now become an absolute must-have for all my proposals and more. Hat tip to them for this one. It's so good I always share it whenever I can.

This has now become one of those techniques that has reduced my stress, created calm and confidence. And I think it's probably the most important part of any proposal I write.

It's stupidly simple.

Instead of just describing what a project is, you also describe what it definitely isn't. Right there, side by side. This, not that.

It sounds obvious when you put it like that. But most of us don't do it. We write proposals that focus entirely on what we're offering, leaving everything else open to interpretation. We assume people will understand the boundaries.

They don't.

Because here's the thing about scope: every positive statement you make can be stretched. If you say you're doing "brand development," someone might assume that includes packaging, signage, vehicle graphics, and a complete website overhaul. If you mention "strategic thinking," they might expect a full business plan.

But if you say what you're not doing alongside what you are, suddenly everything gets much clearer.

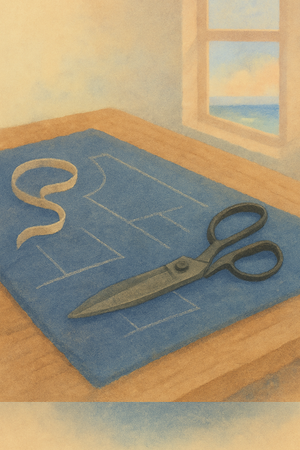

Two Columns, Zero Confusion

The first time I properly tried this was on a design strategy project for a fintech startup. This wasn't the only thing I used for scope, obviously - there was plenty more detail about deliverables, process, timings, all the usual stuff that hopefully articulates the ins and outs. But I added this right at the beginning, before all that detail, to set really clear boundaries early on.

Because there's no point someone reading through the rest of your proposal if they think you're ruling out something they actually need. Think of it as the opening frame.

Instead of just listing what I'd deliver, I added a second column:

This project is:

- Research and analysis of current user experience

- Strategic recommendations for product direction

- Key user journey mapping and optimisation

- Clear design principles and next steps

This project is not:

- Detailed wireframes or visual design

- Complete information architecture overhaul

- User testing or validation of existing features

- Technical feasibility assessment or development planning

The effect was immediate. No one asked me to design their entire product interface. No one expected detailed user testing or technical specifications. When they wanted wireframes later, they asked for a separate quote instead of assuming it was included.

Most importantly, I felt confident about what I was promising. No more that familiar dread of "what if they think this means..."

⸻

It works because it forces you to think about where your project lives on various continuums.

Strategic, not tactical. Guidelines, not execution. Planning, not implementation. One brand, not a full product suite.

These aren't arbitrary divisions. They're deliberate choices about what you're best positioned to deliver, what the client actually needs from you right now, and what would be better handled by someone else or at a different time.

And here's what I've found: clients love this clarity. They're not trying to catch you out or squeeze extra work from you (mostly). They just want to know what they're getting. The "not that" column doesn't feel restrictive—it feels helpful.

It shows you've thought about their broader needs, even if you're not addressing all of them in this project. It demonstrates that you understand the difference between what you do and what you don't. That's surprisingly reassuring.

It's Not Just About Projects

I've started using it beyond just project outcomes, too. This is another one where I've brazenly copied the good work of my friends James and James from Berst, who use this so well to help make it clear to a client why they should or shouldn't work with them.

It also encourages clients to compare them with other agencies or offerings who maybe don't have quite as much clarity or confidence about where their strengths really are.

There's something quite powerful about this kind of honesty. I'm not entirely sure what's going on psychologically, but it feels good writing this stuff out. Almost cathartic. Here's an example...

I'm a good fit if:

- You need someone who can work independently

- You want strategic input, not just execution

- You're comfortable with iterative, collaborative process

- You value clear communication over constant updates

I'm not a good fit if:

- You need someone available for immediate turnarounds

- You're looking for the cheapest possible option

- You prefer detailed mockups before any strategic work

- You need extensive hand-holding through decisions

It feels a bit provocative, I'll admit. There's something about explicitly saying "I'm not for everyone" that goes against every people-pleasing instinct to smile and accommodate and never cause a fuss.

But it works like magic. The clients who respond well to that kind of clarity are exactly the ones you want to work with. The ones who don't? Well, you've probably saved yourself a world of pain.

The dog observed this morning, while pointedly ignoring his perfectly good breakfast in favour of something questionable he found on the street during our walk: "Sometimes the most helpful thing you can do is tell people what you won't do. Saves everyone a lot of confusion later."

He's not wrong.

Your Turn to Try This

So, here's what I'd suggest trying in your next proposal:

Start with your normal scope, but then add a second column or section called "This project is not" or "Out of scope."

Be specific about adjacent services you don't include. If you're doing brand strategy, mention you're not doing the actual brand design. If you're doing UX design, clarify you're not doing polished interface prototypes.

Include a rationale for each boundary. "We're focusing on strategy first so we can get the foundation right before moving to execution" sounds better than just "No website design."

Use it for working style too. Be upfront about your availability, communication preferences, and what kind of client relationship works best for you.

Keep it conversational, not defensive. This isn't about what you won't do because you can't be bothered. It's about what you're not including so you can focus properly on what you are.

And if a client pushes back on any of the boundaries? That's valuable information. Either they're not the right fit, or there's a bigger conversation to have about what they actually need.

Since I started doing this consistently, I've had far fewer scope creep situations. Not zero—there's always the odd "quick question" that turns into three hours of work—but dramatically fewer.

More importantly, I go into projects feeling more confident. I'm not constantly second-guessing whether I've promised too much or whether the client expects more than I planned to deliver.

The boundaries aren't there to be difficult. They're there to create space for good work.

And sometimes, the most generous thing you can do is be absolutely clear about what you're offering and what you're not.

Everyone wins when no one's guessing.

— Tom